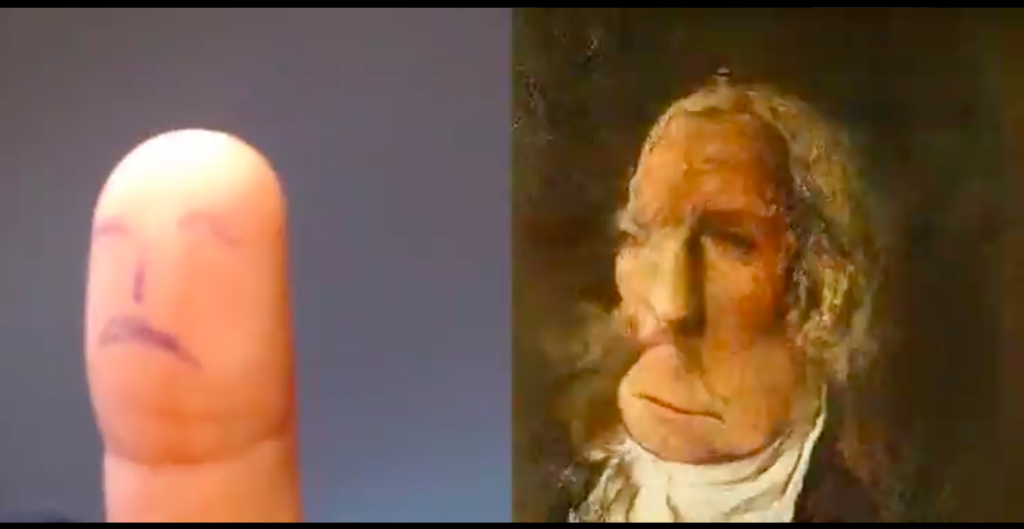

Somehow you recognize faces. And somehow old masters. But somehow it’s also a bit scary. The images are part of Mario Klingemann’s video work 79530 Selfportraits, in which the artist trained a neural network exclusively with portraits of old masters. The artificial intelligence, which “sees” with the help of a webcam, now recognizes faces pretty much everywhere – even if they are only drawn on Mario Klingemann’s fingers with a ballpoint pen. It specializes in facial recognition, so to speak, and tries to make recognized faces as similar as possible to familiar portraits.

Mario Klingemann studied neither computer science nor art, and yet he finds himself somewhere in between with his work. “I was never good at painting,” he says, “but I have visual ideas. That’s why I use machines. “1 His goal in doing this was to develop new things that he only wants or can control selectively. The algorithms are written in such a way that they shape the images without his input, if possible. He wants to be surprised.2 With his neural networks, he succeeds in doing just that, because he specifically trains the network, thereby initiating its creative process, and then looks at the results.

What comes out is an abundance of designs. Thousands are generated, but he selects only a few. Klingemann calls this technique “neurography. The term already exists in medicine, but he gives it a new meaning: He lets the neurons “draw” and thus virtually creates a virtual abstract world in which he walks around and takes pictures. He creates these worlds and spaces himself, mixes them together and makes a selection of results. Like a photographer, he seeks out exciting motifs from the abundance of material. And also like in photography, he varies the detail or the angle of interesting motifs and thus creates different variations of the same from which he can select the best.

Experimentation plays an essential role in his work. Nevertheless, he needs an idea of what the final product should look like, so that Mario Klingemann can get closer and closer to this idea and at the same time expand it with his experiments. After all, his goal is to develop images that are new, and not just reminiscent of the existing and familiar.3

Many of the images created with this technique are reminiscent of surrealist works. The dreamlike quality is easy to recognize. His work is also associated with that of Max Ernst, who tried to find new forms with his Frottages. Max Ernst was interested in finding proposals that were not in his own repertoire – a very similar goal to the one Klingemann is pursuing today, only with a different technique, respectively with a different tool. In Max Ernst’s work, the creation of images is much more in his own hands. Mario Klingemann has employees. The computer creates for him according to order, Klingemann is the client and decision-maker.

In principle, this way of working by Mario Klingemann is nothing new. Artists have always had employees and assistants. However, Klingemann uses a neural network that, according to some people’s understanding, thinks for itself. Should Mario call himself an artist duo? Is it the neural network or Mario Klingemann who is creative? Which of the two is creative? A question about the authorship, which perhaps arises the longer the more with this approach.

In any case, another interesting aspect of Mario Klingemann’s work is that he asks different questions from the perspective of an artist than those that scientists pursue. His work thus has the potential to take the medium and its possibilities further.

It is still questionable whether the portraits created by the machine according to an algorithm are really portraits in the classical sense. Can the neural network capture the character and feelings of a person as a human being, and probably even more so a portrait painter or photographer, is able to? Mario Klingemann’s artificial intelligence does not address this aspect. Rather, it applies the way old masters painted portraits to the images he is looking for. What exactly the criteria are, however, according to which the artificial intelligence decides, we can at most guess after studying the resulting pictures in detail, but never conclusively determine. And only Mario Klingemann can intervene and select those portraits from the mass of images that most closely reflect the character of the person. Just as he also decides which pictures are interesting.

Mario Klingemann says that the development of human culture has always run parallel to the development of tools. Thus, it actually only makes the next logical step. And as with any tool, the use of it needs to be learned before masterpieces can be accomplished. Mario Klingemann thus sees artificial intelligence more as a tool than as an independent cognitive unit.

All the tools we have can be used to produce art, so why not machine learning? Photography also frightened artists in its early days, because the meaning and usefulness of their previous work was jeopardized in one fell swoop by the tool that achieved their aspirations better than they were able to do with painting. In the end, however, it became clear that photography was more of a blessing than a curse. Painting continued to evolve, literally racing through several styles within a few decades.4

Whether machine learning will have the same impact on the arts – it can create not only paintings, but also music and much more – remains to be seen. In any case, Mario Klingemann’s work can be used to discuss many of the current pressing questions of art today. In this respect, we are pleased to be able to announce a lecture by him here.